Accidentally blinded in1922, Sidney Hull moved to our village just so he could commute more easily to his job at Western Electric. But, his impact on our town would be long-lasting.

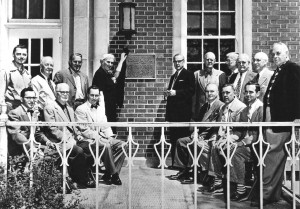

Sidney M. Hull Plaque

In 1922, Sidney Hull was a 31-year-old chemist working in the research laboratory of Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works in west suburban Cicero. One day, an explosion ripped through the lab, blinding Mr. Hull.

Following the accident, Western Electric continued his employment as the company’s research librarian, a post which he held for 23 years. However, he had to find an easier way of getting to his job. So, in 1923 he and his family moved to Western Springs where he would have easy access to the Burlington train, which stopped right at Western Electric. His wife once related how he would count the number of steps from the station to their home each night.

Sidney Hull

Prior to moving to the village, the Hulls were not aware that the hardness of our water was keeping many other people from locating in Western Springs. According to some reports, the water corroded distribution mains, house plumbing, and fixtures. As a result, every house had a soft water cistern for washing and almost everyone had a filter. At night, the bottom of the filter had to be scraped and rinsed, and freshwater was added. If unfiltered water was used, “… beans turned into little black pellets and coffee had a strong acrid taste”.

Mr. Hull, being both a chemist and, as an unpaid village trustee, began looking into the water situation. He discovered that the natural springs, from which the village derived its name, had dried up in 1882, shortly after the Village had begun drilling a well and installing water mains. The historic water tower, itself, was built in 1892.

Western Springs Water Plant – Circa 1954

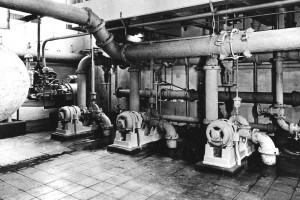

Water Plant Interior – circa 1955

Over the years, there was always ample well water that was safe to drink. But, its high mineral content caused residents to complain to the village. As a result, more than 50 test holes were bored over a 15-year period to locate a higher quality water source. But, these efforts had yielded little success.

After looking at a variety of solutions, including the costly option of importing Lake Michigan water from Winnetka, the Village Board agreed with Hull’s recommendation that a water softening plant should be built at the corner of Johnson and Hillgrove.

Water Plant Interior – circa 1955

Mr. Hull, the chairman of the Water Committee, was instrumental in its construction. Although he could not see, it was reported that he memorized “… every wire, nail, and screw that went into the building” and that, using his mental image of the blueprints, was able to discuss design issues with the architects, often correcting them in the process.

The building went into service on January 2, 1932. And, during the first week, Mr. Hull did not leave the building even once, preferring to stay on-site to make sure everything was working as designed. As a result, Western Electric gave him a one-week leave of absence. During this time, he slept on a cot in the building, with his meals being brought to him by his wife and three children.

By all accounts, the plant represented “leading edge” technology in 1931. In fact, representatives from other communities with similar water problems often came to inspect the new facility as a model for their own towns.

In 1951, Sidney Hull passed away. However, in recognition of his dedication to improving the water system, the Village Board invited his spouse, Nina Hull, to help dedicate a plaque in his honor in 1954. Today, the plaque is still visible next to the building’s front door, located on the corner of Hillgrove and Johnson Avenues.

Since then, numerous improvements have been made (and continue to be made) to the village’s water system to accommodate population growth and new technologies. However, Sidney Hull’s contributions serve as a reminder of how much we owe to these early residents. Although blind, he had the foresight to find a way to improve every resident’s quality of life.