In the 1920s, the nation’s newspaper staffs were dominated by men. But, one diminutive young woman from Western Springs changed all of that.

Ione Quinby – circa 1930

If you wanted to be a newspaper reporter in the 1920s, you had to be a man. But someone forgot to tell that to Ione Quinby. Raised in Western Springs, she studied journalism at Northwestern University. Although she briefly worked for the weekly Western Springs Times, her first real job was with a major advertising agency in Chicago.

While the pay was good for those days, journalism beckoned. So, she decided to take a big cut in her weekly salary – from $35 to just $15 – in order to work at the Chicago Evening Post. But, unlike most female writers, she wasn’t assigned to the society pages. Instead, she covered numerous murder cases, gangsters, and visiting dignitaries. Her male colleagues grew to accept her as “one of the boys.”

Quinby said that her most memorable interview was with Al Capone during his trial for income tax evasion. She said that Capone, noting how little she was (5’1”), offered her half of his candy bar. Afterward, Quinby wrote that he “…was very pleasant and courteous” to her. Later, she even covered the lavish wedding of Capone’s sister.

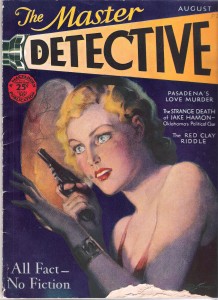

1930 Magazine with a Quinby Story

During this time, she also wrote articles for crime magazines, which were extremely popular in the 1920s and 1930s.

Quinby even took an assignment from her editor that involved riding atop an elephant dressed as the Queen of Sheba, as well as one where she had to learn the ropes as a wild animal trainer.

Quinby had a knack for becoming fast friends with various dignitaries and VIPs. She interviewed Eleanor Roosevelt, Jean Harlow, Mary Pickford, Amelia Earhart, and Jack Dempsey. And, while she was known to dine with royalty visiting Chicago, she was equally adept at interviewing murderesses. She also had a soft spot for the people she met along the way. For example, she would regularly bring a young girl to visit her mother, who was serving a life sentence … even arranging for the two to have Thanksgiving dinner together in prison.

In 1932, Quinby married Bruce Griggs, a freelance writer. But, a short time later, she lost her job when the paper closed its doors. And, in 1933, her husband died in a tragic automobile accident. She never remarried.

Without a job and without a husband, Quinby (now Mrs. Griggs) began freelancing, writing stories for True Confessions Magazine and also producing a book entitled “Murder for Love,” a detailed account of seven women who became murderers.

Quinby as the Queen of Sheeba – 1930

In 1934, she was hired by the Milwaukee Journal and began an entirely new career by writing a daily advice column entitled, “Ask Mrs. Griggs.” And, for 50 years she provided “no-nonsense” Midwestern counsel that educated and entertained Milwaukee residents of all ages. She would sometimes receive thousands of letters in a week, reading them all without the help of any staff. Her work was recognized with numerous awards from her peers.

Despite her success, Mrs. Griggs lived a very simple life. She resided just a short distance from the newspaper office in an apartment hotel and walked to work every day. And, while she never learned to drive, for many years she would take the train back to Western Springs every two weeks to visit her family at 4052 Forest Avenue.

Mrs. Griggs almost always wore a hat, even at her desk. See photo. She rationalized this by explaining that a reporter always has to be ready to dash out the door to cover a story. She was also well-known for never revealing her age.

Ione Quinby Griggs – circa 1980

Griggs’ remarkable career concluded in the mid-1980s and, in 1991, she died at the age of 100. But, that was not the final page in Mrs. Griggs’ life. Although never highly paid, Mrs. Griggs was very frugal. Upon her death, she left the bulk of a substantial estate to fund journalism scholarships for women at both the University of Wisconsin and Marquette University.

Genevieve G. McBride and Stephen R. Byers have written a book about Mrs. Griggs that will be published by the Marquette Press.