By John Devona

In 1953, an African-American couple wanted a home in the Forest Hills subdivision. But, some tried to keep that from happening.

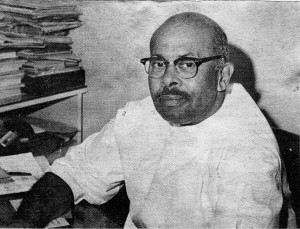

Arthur Falls, MD – circa 1968

Arthur Falls was the African-American son of a postal worker and a dressmaker. In 1925, he graduated from Northwestern University’s School of Medicine and opened an office on Chicago’s south side. He joined the staff of Provident Hospital which, at that time, was the only medical facility in Chicago accepting black physicians.

By all accounts, Arthur was a first-rate doctor. In addition to handling numerous obstetrical cases, he was known as an excellent thoracic surgeon. In fact, he would eventually become the hospital’s chief of staff and achieve international renown. His wife was also a respected psychiatric social worker.

While medicine was Falls’ vocation, he was also an early civil rights proponent. However, Falls did not feel the solution was to protest discrimination through marches. Instead, he focused on helping disadvantaged minorities by opening doors to higher education. In fact, a group he founded was credited with getting an estimated 6,000 minorities into medical schools. Falls also filed lawsuits against four Chicago hospitals, after which most hospitals began accepting both black doctors and black patients.

In 1952, Falls attempted to buy a residential property in north suburban Deerfield. However, this was blocked when citizens prevailed on the park district to purchase the property and the courts upheld the legality of their action. So, Falls applied for a permit to build a home at 4812 Fair Elms in Western Springs. But, the Forest Hills Improvement Association opposed the move due to concerns about the potential impact on property values.

While six village ministers met with the Falls to assist them in their efforts, a petition was circulated requesting the Park District to purchase the property for future use, similar to what had been done in Deerfield. However, in the interim, the Village issued a building permit to the Falls. After more legal wrangling, the courts rejected the Park District’s condemnation efforts as being racially motivated. And, in July 1953, the town’s voters rejected a subsequent Park Board referendum which proposed the purchase of a larger tract of land, including the Falls’ lot.

In December 1953, Dr. Falls and his wife moved into their new home without incident. According to one account, “Property values in the neighborhood continued the spectacular rise characteristic of the times; many new homes were built in their area.” Other accounts describe how Dr. Falls joined St. Cletus Parish and, later, St. John of the Cross. Mrs. Falls, the daughter of a minister, continued to attend a Congregational church in Chicago.

Dr. and Mrs. Falls gradually built a circle of friends and neighbors, as would any new residents. Some, even among their former opponents, wondered what all the fuss had been about. During the ensuing years, the Falls traveled overseas extensively. And, Dr. Falls continued to receive numerous awards and honors, both for his human rights efforts and his medical acumen. In 2000, Dr. Falls passed away at the age of 99. He was buried from St. John of the Cross church.