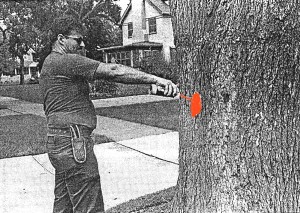

In the 1980s, every resident dreaded seeing a reddish/orange dot on a parkway tree. Each one marked the end of a wonderful shade tree.

Public Works employee marks a diseased elm tree – 1989

In the 1890s, forward-thinking village fathers began planting parkway trees in the yet-to-be-developed neighborhoods of Western Springs. One of the most popular trees was the American elm which, when fully matured, formed a beautiful green arch above the street. In fact, by 1955, there were nearly 3,500 American Elms lining the village’s streets. It was in that year, however, that the village’s first case of Dutch elm disease was spotted at 3830 Wolf Road. This resulted in the removal of four trees. Many more would follow, often as many as 80 to 90 in a single year.

Despite the name, there are no “Dutch elm” trees. The disease got its name because it was first detected in the Netherlands. By 1940, it reached the United States, where close to 50% of the elm trees eventually succumbed to the disease. The disease is actually a fungus that moves from the roots of one elm to another. The fungus is also transferred by tiny elm bark beetles, which can fly a mile or more. The fungus produces a thick substance that blocks the tree cells that transport water. The first indications of the disease are leaves that turn yellow and die. Eventually, the entire tree dies, usually within a year or so. However, by quickly cutting down and removing infected trees, the spread of the disease can be slowed.

Dutch elm disease seems to accelerate following periods of drought. That’s because diseased trees are not as readily identified since even healthy trees can have some yellow wilting leaves. The old method for controlling the disease was the use of DDT spray. However, when this was stopped for health reasons, the village turned to the use of Arbortech 20-s, a fungicide that could be injected into the tree. But, it was expensive and had only limited success. Today, quick removal of infected trees remains the best way to slow down the disease.

To replace the diseased trees, the village has turned to other species that are immune to the disease. Among these are hybrid elms developed by the Morton Arboretum. While having a shape very similar to the American elm, they are immune to the disease. Ironically, in the early days, some of the diseased American Elms were replaced with Ash trees, which, years later, are facing their own threat, the Emerald Ash Borer. But, today the village is making a concerted effort to plant a larger variety of tree species so as to limit the long-term risk of losing large numbers of trees to a single infestation.